Have you ever wanted to cancel a subscription or switch products only to realize it's too expensive, too much hassle, or otherwise annoying? Then you've encountered lock-in effects. One of the most prominent examples of this is the choice between Apple and Android. When did you decide on your smartphone system, and how often do you switch between worlds? Probably never. How do you build that kind of loyalty? That's what I want to talk about today. I'll introduce you to 9 types of lock-in effects and show you examples of how you can use them to build loyalty.

⚠️ But first, a warning: lock-in effects can be very effective, but bear their name for a reason. If you overdo it, your customers will feel trapped and frustrated, thus damaging the brand, and in the worst case scenario, customers won’t even try your subscription in the future out of fear of never being able to leave.

- You can see this with business software, for example. Changing it often costs so much that companies continue to use bad software instead of switching to a better solution

- To be honest, I was a little unsure about writing this post because some of these tactics become “dark patterns” that I don’t want to recommend

- Nevertheless, I believe that you should be aware of these methods, after all they’re used by leading vendors and possibly your competitors. However, critically examine which methods you feel comfortable with

Recommended read: 3 clicks to cancel: the new legislations that are forcing publishers to rethink their subscriber unsubscription journey

Now here are 9 types of lock-in effects with real world examples:

1/ Ecosystem (compatibility)

In this game, Apple is the master. Those who own an iPhone often also have a Mac, Airpods, an Apple Watch, iCloud, Apple Music, and other hardware and services. Everything is seamlessly interconnected, and those who decide to switch can no longer use some of it at all or only with significant restrictions.

Psychologically, the “sunk cost fallacy” comes into play here, which says that people often irrationally invest even more money in something because they’ve already spent so much in the past. This works on the one-armed bandit as well as on subscriptions.

In the video game sector, this effect also ensures that customers often remain loyal to a manufacturer for decades. Whenever a new generation of consoles is launched, there’s a risk that customers will switch to a competitor. That’s why Sony, Microsoft and Nintendo often emphasize backwards compatibility in their consoles. When the Playstation 2 was launched, there were already over 7,000 compatible games from the previous console and fans could sell their Playstation 1 and seamlessly swap it for the successor.

- What does this mean for me? Consider offering complementary products to your subscription that work together to provide greater value.

- What can you do about it? One person’s lock-in effects are another’s barriers to entry. But you can actively do something to react to this. For instance, you can ensure that competitors’ hardware or software is compatible with your own tools. One example is Microsoft who, at some point, abandoned its foreclosure strategy and has since offered an (almost) equivalent Office package for Apple’s competing operating system. In the end, both benefit from this.

2/ Data

I probably don’t have to explain to anyone that data is the gold of the digital economy. But perhaps you aren’t yet aware of how it can be used to create lock-in effects.

I recently noticed this with Airtable. It’s a very user-friendly software where you can drag and drop to create databases without the need for software developers. For example, I used it to build my database for client projects and my hour tracking workflow. However, as easy as it is to create databases, it’s difficult to get the data out again. The only export option is a CSV table, which easily leads to bugs, and links between different databases get lost. I have therefore abandoned my planned move to Notion for the time being.

In general, this strategy is ubiquitous in B2B software. Due to proprietary formats and sometimes non-existent interfaces, vendors make it difficult to move to other systems and a changeover quickly swallows up tens of thousands of dollars.

To give another example, did you know that Amazon Prime includes a photo cloud in addition to free shipping and streaming services? Very cool in itself, but while I could easily pause my Netflix subscription, Prime causes me to keep my subscription because I don’t want to back up 3 terabytes of photos to save 3 months of subscription fee.

- What can you do if your competitor uses this strategy? You could provide interfaces through which users can transfer their data, offer a low-cost migration service, or provide step-by-step instructions on the website.

3/ Personalization

This point is closely related to the previous one, but while with Airtable and Prime I uploaded my data myself, here we’re talking about data collected in the background.

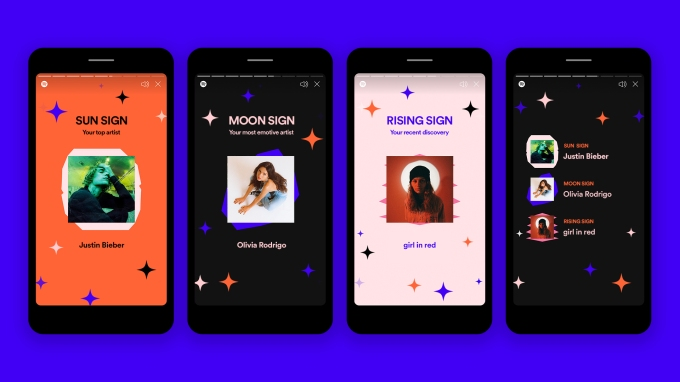

Spotify is the prime example here. The app knows my music tastes over the last 10 years and uses this data to recommend new music and create playlists tailored to me. Spotify itself says that its promise is not just access to music, but more importantly discovery. If I switch to Apple Music, the app has to get to know me all over again before it can make recommendations on a comparable level.

Even with Blinkist, I create a reading/listening list and build up a playback history. When I switch to the competition, I’m likely to be suggested many books that I’ve already listened to and that Blinkist would have automatically filtered from my recommendations.

I imagine this factor might become less important in the future, after all the signals and algorithms are getting better and thus faster. TikTok already knows me better after 30 minutes than Instagram does after 3 years.

4/ Network effects

Some services become more valuable the more other people use it. The best way to see this is the strong concentration tendencies in social media.

Just how difficult it is to break through this effect can be seen with X. Although many users are dissatisfied, they remain loyal to the service because they have built up their reach there over many years, and they don’t want to lose it.

That’s where Meta comes in with Threads. With the ability to bring contacts from Instagram, they start directly with network effects and were able to gain 100 million users in a very short time. However, the rapid decline in engagement also shows that the network is only valuable if users are also active.

5/ Price guarantees

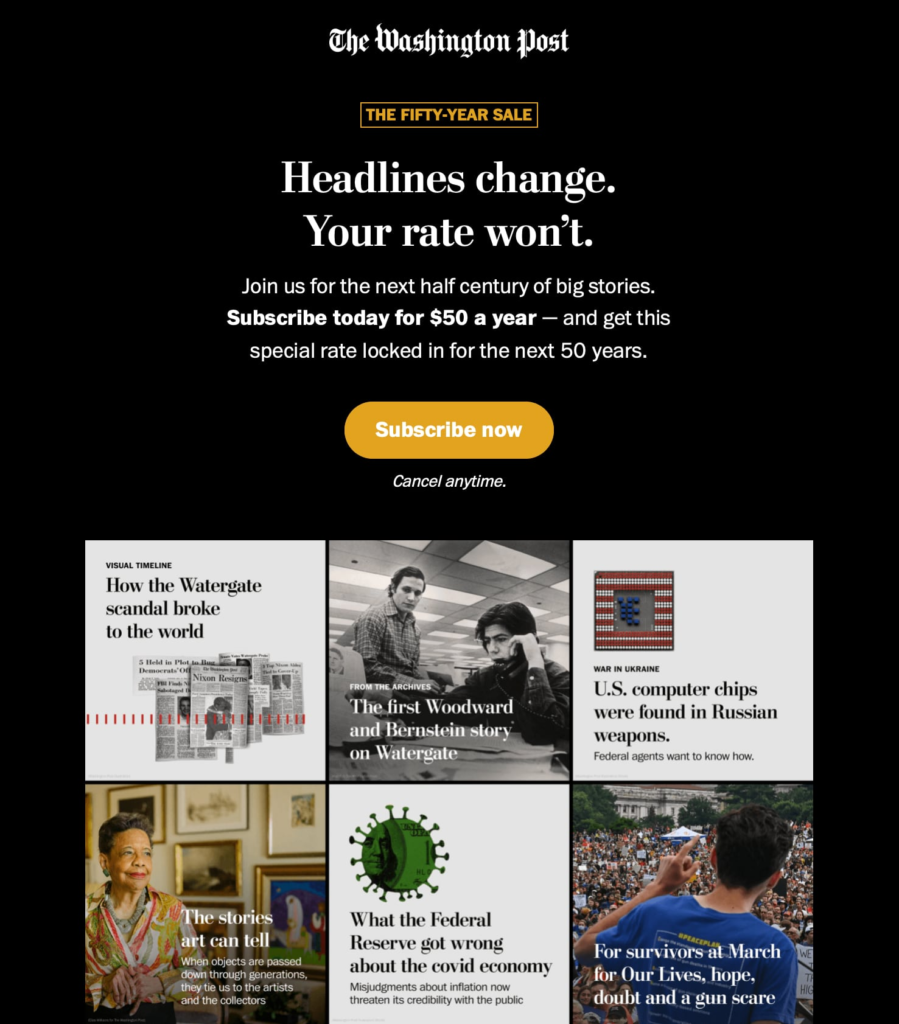

In our everyday lives, we notice how quickly everything becomes more expensive. This makes old contracts all the more valuable. This can be the Berlin flat lease from the 90s or, as with the Washington Post, a price guarantee for the next 50 years. For the Watergate anniversary, they offered a subscription for $50 per year with a price guarantee until 2072 – which, importantly, expires if I cancel or pause my subscription.

But beware: this makes sense only in individual cases. After all, price increases are often necessary to compensate for rising costs.

Nevertheless, I find the idea of raising prices primarily for new customers and keeping prices for existing customers slightly below those for new customers charming.

6/ Credits

Has anyone ever asked you for audiobook tips because they still have 15 credits to use up at Audible? Behind this is their very unusual subscription model. Every month you get 1-2 credits that you can exchange for audiobooks. If you don’t redeem them, you can still use them in the following months, gradually building up credits that you would lose if you cancel. So while you can’t decide on 15 audiobooks, another month goes by and it becomes 16 credits.

7/ Additional users

For many subscriptions we don’t use them alone, but together with friends, family or colleagues. Netflix and Disney encourage this via different user profiles, Spotify offers family subscriptions and business software is usually charged by the number of seats. So anyone who is now thinking about cancelling cannot make this decision alone, but must consult all the people affected.

Another example is Blinkist who gives me a partner account with every subscription. If I now invite my girlfriend, then in the best case they’ve gained two fans and even if I no longer feel like the subscription, I would keep it for my girlfriend.

8/ Bundling

Am I solving a single problem for my users, or many different ones? Here we come back to my example from above. I can cancel a movie streaming service quickly and easily, but if my photo cloud and my e-book subscription are also integrated into the same subscription, then the hurdle is much greater.

What Amazon has achieved with Prime can also be found with the New York Times. In addition to news, they also offer games, product tests and recipes in the bundle. If I now want to switch to another provider, I don’t need one alternative, but four.

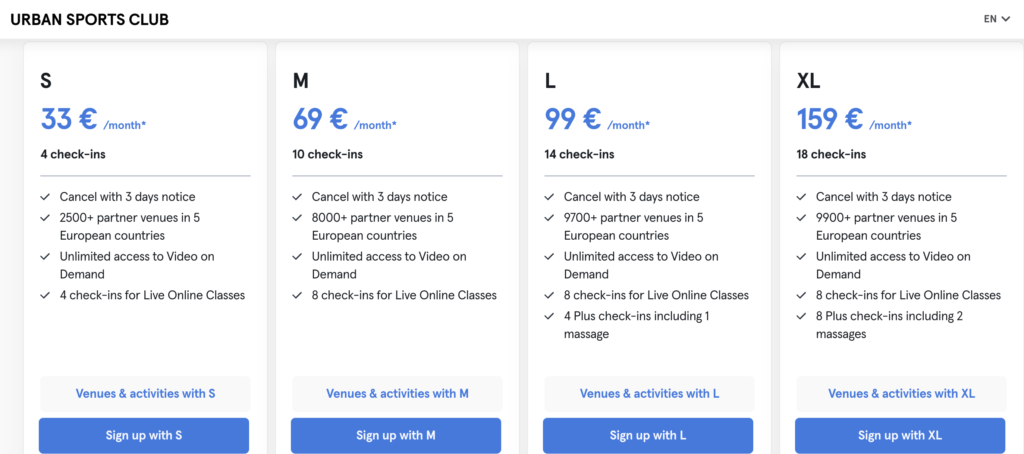

The Urban Sports Club also relies on bundling. Torsten Müller said in an interview that customers who always go to the same provider often don’t stay with them for long. But if you do several sports with different providers, you won’t find an equivalent alternative on the market.

9/ Status

Here we come back to Apple. The iPhone is not just a device, for many it is a part of their personality. It makes you feel part of a creative class and shows others that you don’t have to look at money so much. There used to be well-known advertising campaigns that compared Mac and PC users in an ironic way, creating two camps. This status also leads to a lock-in effect, because once you have publicly identified yourself as part of one camp, it will be harder to change camps later on.

Public commitment reinforces this effect. Can you get your fans to style your tote bag? Or take their friends to your event? Or publicly recommend you on social media? All of this contributes to public commitment and identification with your brand.

Wild digression, but street gangs also take advantage of this lock-in effect. If you have the logo of your gang tattooed on your face, you will hardly be able to join the competition afterwards.

Can you think of any other examples or other types of lock-in effects that you've observed with subscription providers? And what's your take on these effects? Effective customer retention or outrageous gagging? Write to me! And subscribe to Lennart's newsletter here.