There are plenty of brilliant articles covering methodologies for launching new products. Even ChatGPT will give you a comprehensive list of the work involved. But not enough is said about the other side of product launches: the internal mindset shifts that are required and the daily soft skills needed. So here are my human-first learnings of launching FT Edit at the Financial Times.

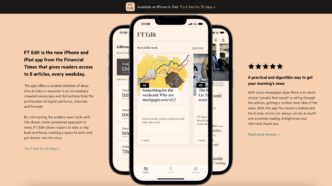

FT Edit and the Financial Times

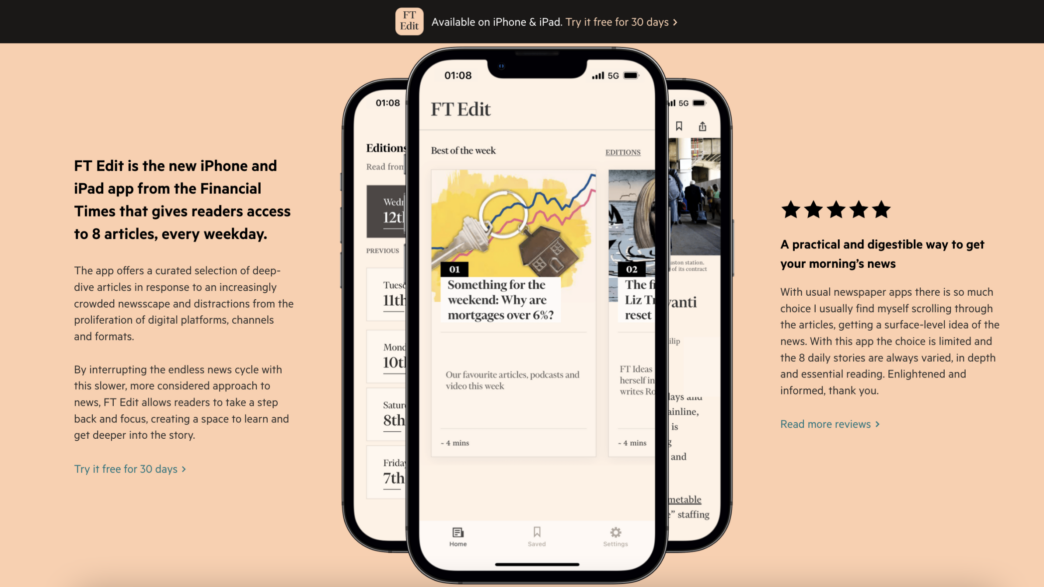

FT Edit is a new app by the Financial Times that offers 8 in-depth articles a day. The app aims to replace the endless scrolling on social media and news sites with more thought-provoking reading time. It’s the first new app the company has launched in a decade.

Contrary to popular belief, I think there’s virtue in launching something new on a decades-old foundation. The team felt like a startup, while our 135-year-old organisation is far more comfortable launching new products now than a year ago. Here is what I’ve learnt:

1. Identify your baseline

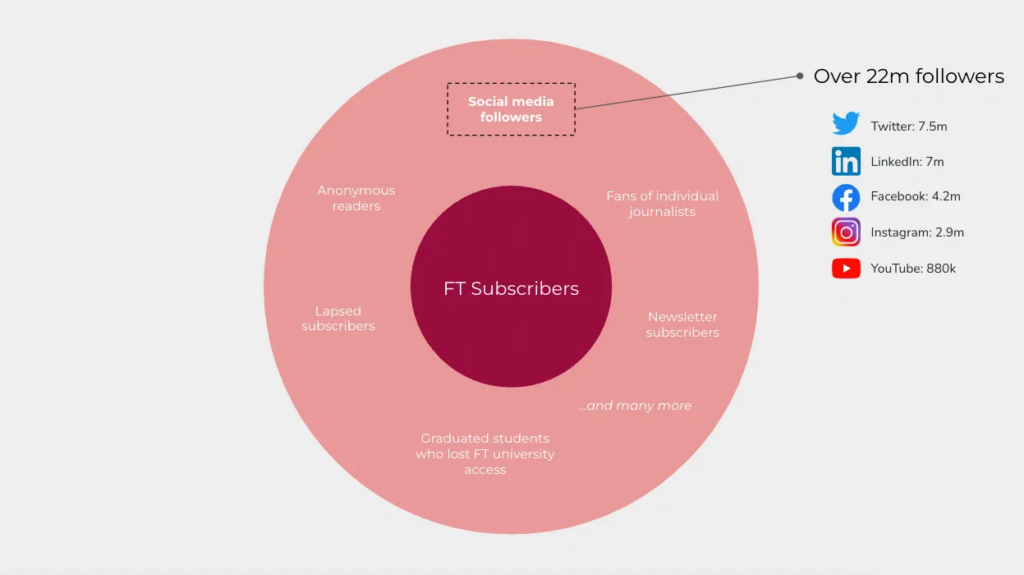

We had a good starting point – the FT already had a strong internal belief that:

- FT content has much larger audience appeal than our subscriber base (look at our 7m LinkedIn followers), and

- It’s hard to attract new customers at scale with our price of +£35 a month.

But launching new products requires a new mindset. Drawing on my previous experience launching new features at Google Arts & Culture and running my own startup, I knew a lot needed to change.

Being an intrapreneur always requires cautious patience which can, at times, clash with an entrepreneurial spirit. I mapped in my head the areas that were critical to change immediately; areas I could change later; and things I needed to accept and appreciate.

2. Pick your battles

When launching a new venture, you need to be ready to make decisions every minute. Inevitably, there will be arguments — a positive sign you have surrounded yourself with thoughtful, critically-thinking individuals. However, as you have limited time and energy, being wise on which battles to pick is essential for success (and your sanity).

My rule was that I aimed to influence situations that were vital for validating product-market fit.

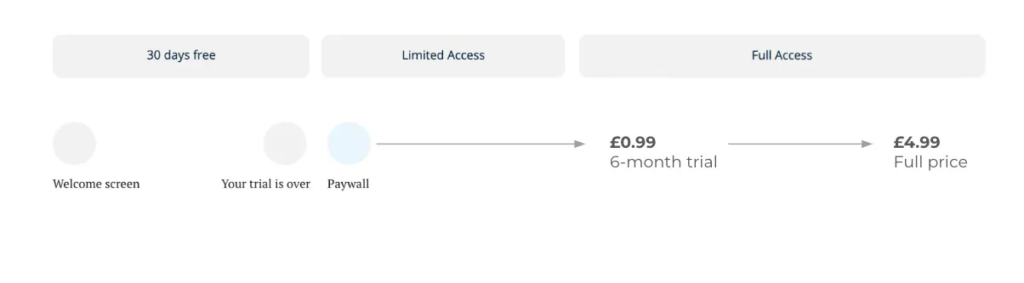

For example, the FT’s initial understanding of a low-cost product was £19 a month. While it’s nearly half the price of the current subscription, it’s still more expensive than any other news subscription on the market. Our main job with the FT Edit was to understand if users would engage with the product and be willing to pay for it, at scale. If we set a price that was too high, we wouldn’t know if it was the proposition that didn’t resonate with readers, or the price was too high for that proposition. It was a “make or break” decision and we decided to push the organisation to agree on a cheaper price (currently £0.99 for the 6-month trial).

As you have limited remit (and energy) as a Product Manager, there were areas that I challenged but decided to park for later. These were mainly areas which, prior to launch, we had no data on, therefore it was pointless to engage in long discussions. For instance, we took the decision not to include new articles on the app during the weekend; instead we would feature “best articles of the week”. One year after launch, we are seeing weekend engagement rapidly decreasing for new users and the team is now revising this approach.

Finally, there were the situations I had to work with. In our case, it was whether we could launch a fake-door paywall instead of spending time developing a working paying solution. One of the worries was it would impact our brand. I sensed that the organisation was not ready for this type of crude experimentation. A year later, this is no longer the case!

3. Get your team comfortable with ambiguity

There will be many moments in the new product development journey where you need a team that is comfortable saying, “I don’t know, let’s try and see” or “Yes, why not”. It’s an attitude that is significantly different from the requirements of a regular job, no matter the department. In a normal setting, you are praised in your job if you know all the answers and you are detail-oriented.

Doing new product development requires the opposite virtues: distilling signals from noise, and knowing what’s important to focus on right now, and what you should worry about later.

For example, the FT Edit experience is no different for users who have been paying for 2 months or for 8 months. We decided that life-time value is something we will optimise for only if we validate there are enough users ready to pay for the product after using it for a month. This is not to say that long-term retention is not important, but we made the conscious decision that our resources were limited, and there were more important things to solve right now.

I was lucky enough to be surrounded by people who, although they had no experience in launching new products, were curious and excited and wanted to challenge the status quo. This mentality made our team move much faster.

4. Take the team on a journey with you

If you are someone who has launched multiple new products, you probably have the whole playbook in your head, but don’t assume people from your team will know what’s coming next. It’s the job of the Product Manager to ensure everyone in the team understands the decisions you take and feels confident that we are building the right thing. I aimed to be systematic and transparent on the product decisions I’m making and what would follow based on different results and scenarios. I aimed always to articulate to the team what our product strategy was and why we had prioritised one feature over others.

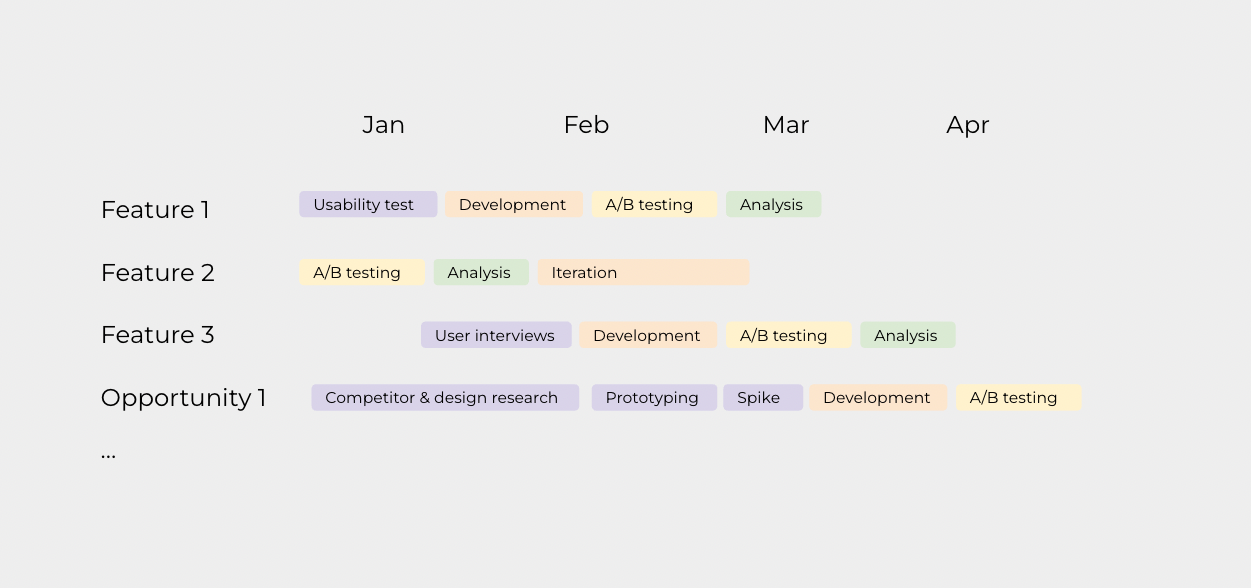

We did a few things that helped tactically: we have a weekly team meeting with everyone working on the project. All qualitative or quantitative research is shared in that meeting, we discuss the results and we make decisions together.

5. Everything revolves around the value proposition

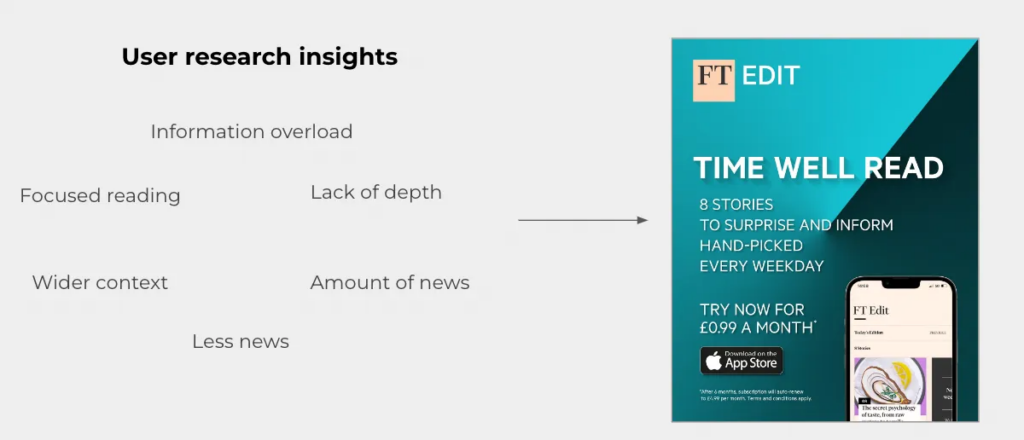

Our team spent months surveying users, doing diary studies and user interviews, before we designed even one screen. Articulating clearly what problems your product solves and where it adds value into people’s lives is the foundation upon which everything else is built. Still, if this information is mentioned once in a meeting and then collects digital dust in a shared folder, it all goes to waste. I quickly understood that this was not a one-off activity. Particularly in the early days, we mentioned the value proposition at every single discussion we had around the product.

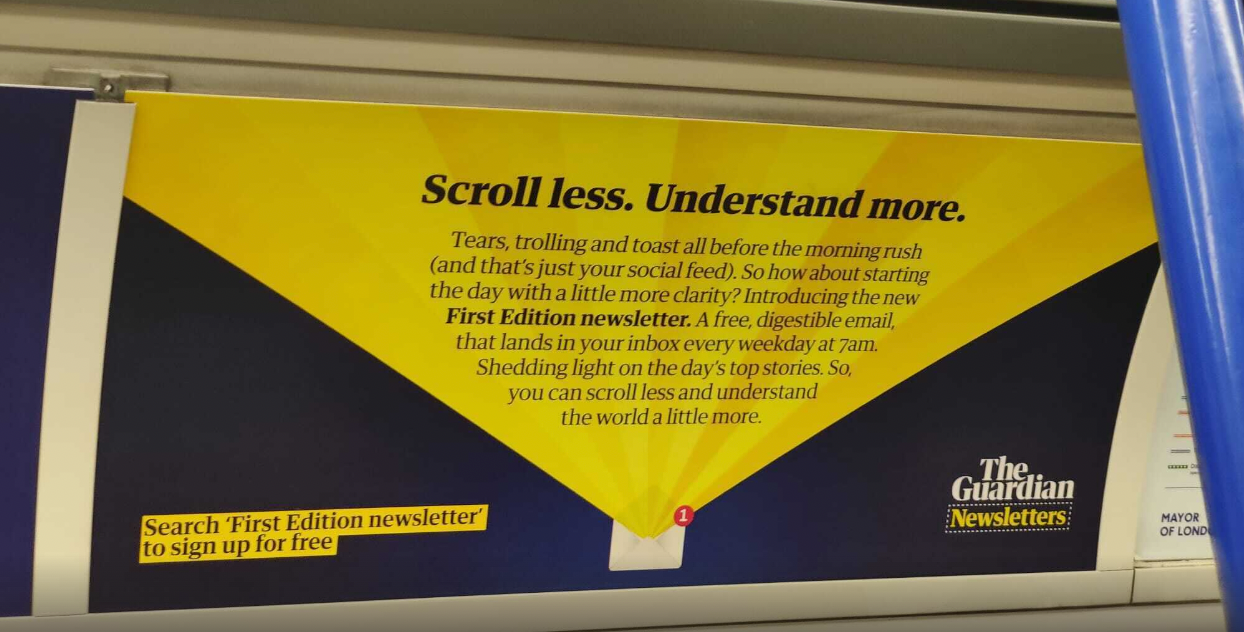

One way we ensured alignment was involving all departments from inception — marketing, brand, PR, editorial, product, technology. They were surely annoyed with me and Maia Bridi (our stellar researcher at the time) asking the whole team to attend user interviews or sit through key insight sessions. We filtered any decision through the lens of our value proposition. This resulted in marketing coining the slogan “Time well read” for our launch in March 2022, as well as editor-in-chief Roula Khalaf describing the app as a way to “Read less, understand more”. It’s exciting to see how little by little everyone is playing to the same tone for a new product you have created together.

> Discover value proposition benchmarks from successful publishers

6. Are we there yet?! Defining success before launch

Another thing that empowered the team to stay focused and move quickly was having a clear definition of success from the very beginning of the product development journey. Reaching product market fit is an elusive term if you don’t know what you want to achieve. In our case, we know we would be successful if FT Edit reached the industry benchmark for Download-to-Paid rate on mobile news apps, and if we did this at scale.

Having a high Download-to-Paid rate with few users would mean we were a niche product; having a lot of users with low willingness to pay would mean we were not offering anything new or valuable.

On the latter, consider how you will reach product channel fit: how to optimise your product to work with the top communication channels your audience is using. It would be a mistake to focus exclusively on growth before you have validated your product is valuable to users, but it’s important to consider embedding one or two growth loops into your product early on. In our case, we over-relied on paid marketing activities at launch which should not be the only growth driver to any new product as marketing budgets are never endless.

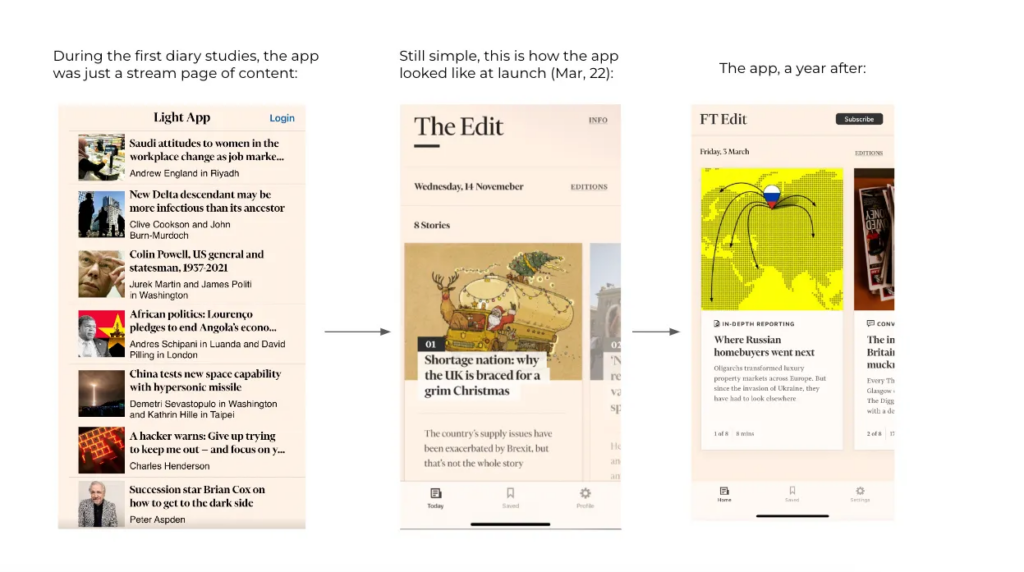

7. The perfect MVP doesn’t exist

It’s a paradox: you cannot create a perfect product, if you haven’t launched a scrappy minimum viable product (MVP) first. The process of new product development is a iterative, sometimes chaotic journey that requires you to launch unfinished products to learn how to make them better. By contrast, the FT has a reputation as one of the most trustworthy organisations in the world for the opposite reason: perfection is the aim with everything we publish. This could easily have created tension between the product and editorial teams.

Luckily, the editors on the app, Malcolm Moore and Hannah Rock, were open-minded, and they trusted me with adopting a new approach to work.

While we kept our perfectionism in the editorial realm, we learnt how to be more experimental with testing our assumptions and launching experiments, from new push notifications to product improvements.

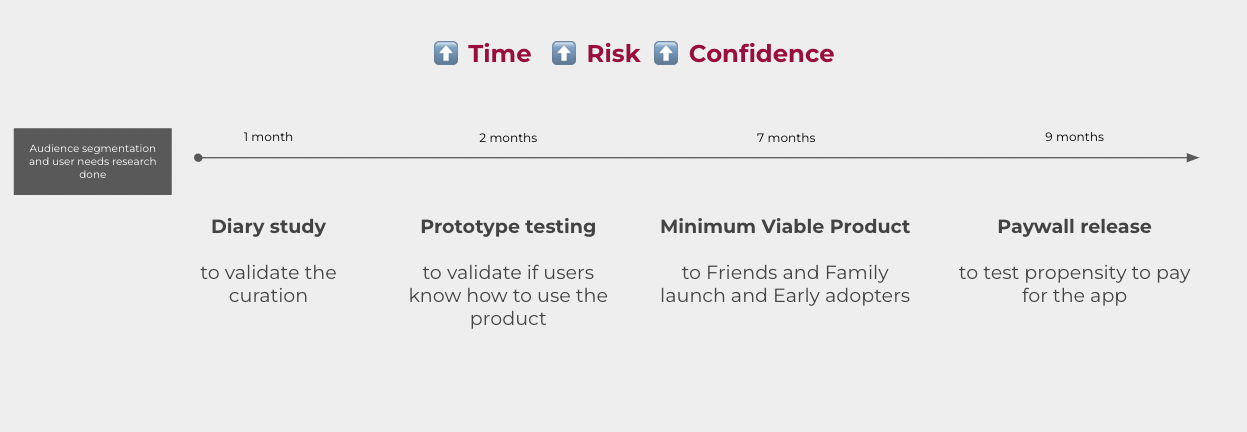

8. Validate your biggest assumptions as early as possible

Before the minimum viable products, there were the minimum viable tests. I often share this article by Gagan Biyani, which discusses a leaner approach to testing new product concepts.

It asks you to list all the things that need to be true for your product to succeed.

FT Edit is an app offering long-reads, we therefore needed to validate if people would be willing to do that long reading on their phones. We did this in a diary study before we had a working product and no user has brought it up as a problem.

You don’t need a team of engineers and extensive A/B testing to validate whether your product has a chance of success.

Once you have that initial validation and knowledge, it becomes much easier to pitch internally for more resources.

Hope this was useful!