Khalil A. Cassimally is Head of Audience Insights at The Conversation, working with editorial, audience, data and engineering to bring more value to more people in more places.

We’ve all seen it: a team wants to know more about its users or customers so it scrambles to create a survey with lots of questions. It hustles to get respondents, eventually compiles the data it gathered, and presents them as a massive slidedeck. And it hopes that among the plethora of collected data, it will find some potentially interesting information.

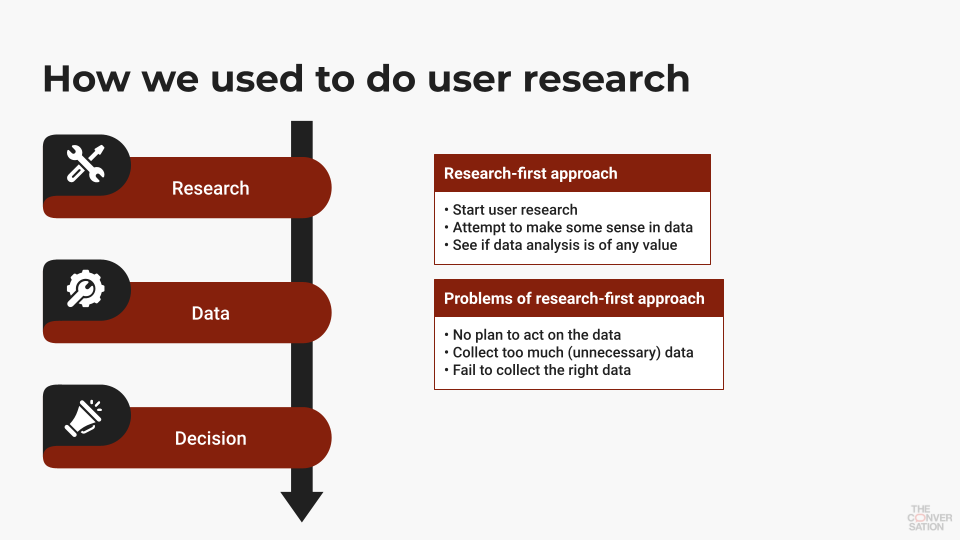

This is the research-first approach to user research

Teams conduct the research first, then they attempt to make some sense out of all of the gathered data, then they try to tease out some of the information that may inform future work (to fix a user problem, perhaps).

This used to be our (the audience development team’s) approach to user research within The Conversation’s UK newsroom. And it was not ideal.

There are three main reasons why the research-first approach to user research is not ideal:

- Few to no actions come out of the research. Because there are no real plans to take action – to create something – based on the data the research gathered. Teams may learn more about their users – great! – but then what? How are they using the new knowledge? What is the point of doing user research if nothing comes out of it?

- Failure to collect the right data. Sometimes teams will be able to tease out some valuable information from the research. Only to realise that it’s not enough to properly inform future work. Here’s something that happened to us: we were analysing data collected from a survey and began to suspect that a particular audience segment became more engaged newsletter subscribers. So we set out to properly define that segment, only to realise that we didn’t have age group information. Turns out, the survey never asked respondents to select their age group. We failed to adequately define the segment because we didn’t collect the right data.

- Collecting too much unnecessary data. Teams cast a wide net to collect as much data as they can. But at the end of the day, only a sliver of all collected data, if that, will hold some value. It’s a waste of resources for teams and also a waste of time for users.

What is the point of doing user research if nothing comes out of it?

The good news is: there is a better, and more efficient, approach to user research. One that is premised on informing actions. We’ve been using it for the past year. It’s the decision-first approach to user research.

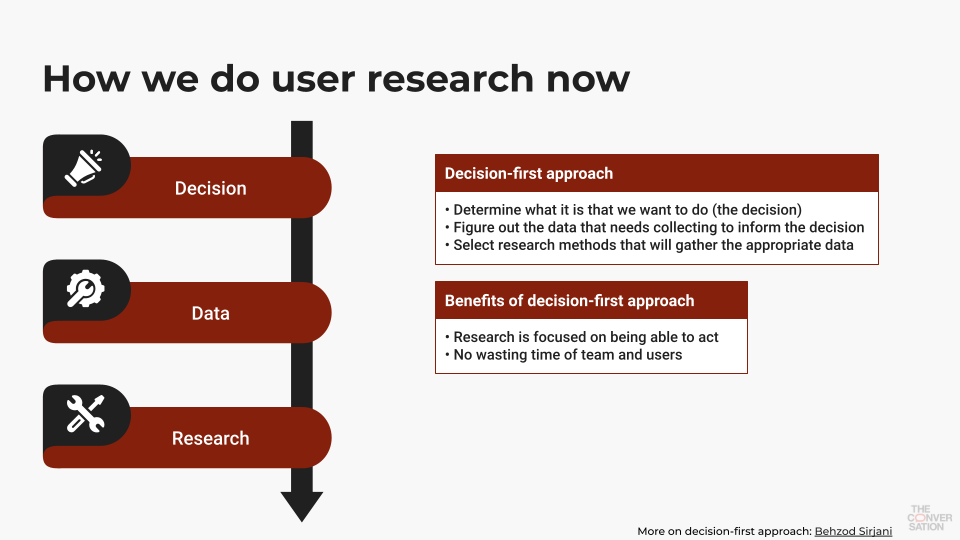

The decision-first approach to user research

It’s essentially the research-first approach flipped on its head:

- Make a decision first – determine what future work your team or organisation wants to do

- Figure out the data that needs collecting to inform the decision

- Select research methods that will gather the appropriate data

Here is an example of how we used the decision-first approach to user research

The Conversation is one of the most prolific publishers of climate content in the world. We publish 150-200 climate articles every month; the monthly viewership of our climate content is at least 2.5 million.

In the runup to COP26, a major UN climate summit in 2021, we asked ourselves: what is it that we can do for that audience? We figured this out at the decision layer.

Make a decision first

To determine what we wanted to do (what decision we wanted to make), we asked ourselves a few questions:

- What is the problem we want to solve for users?

- How can we solve that problem?

- Is this aligned with our business goals?

- Is this aligned with our mission?

And we came up with this decision:

We want to create content and/or products that address the needs of our climate readers so that our COP26 coverage is more valuable to them.

With the decision made, we needed to think about the data we would need to inform the decision – i.e. what information we needed to deliver the decision. We figured this out at the data layer.

Figure out the data that needs collecting to inform the decision

To determine what data we needed to inform the decision, we asked ourselves another set of questions:

- What are the needs of our climate readers?

- What is it that we need to show editors to inform their commissioning?

And we came up with this set of data that we would need to collect:

- List of needs of our climate readers

- Hierarchy of those needs

- How those needs are currently served by our climate coverage

So, we had a decision and we knew what data we needed to inform that decision. Our next step was to think about how to gather the data. We figured this out at the research layer.

Select research methods that will gather the appropriate data

To determine what research we needed to conduct to gather the necessary data, we asked ourselves yet another set of questions:

- How do we get a basic understanding of the needs of our climate readers?

- How do we know which needs are greatest and which needs are less great?

- How do we find out the extent to which our current coverage matches those needs?

And we came up with research methods specific to those data collection requirements:

- 1-1 interviews to get qualitative data about needs

- Survey to get quantitative data that enables ranking of needs

- Analytics to get quantitative behavioural data (in part to validate what survey participants told us)

- Manual tagging of climate articles to map content production to needs

By this point we had the decision, we knew what data we needed to collect to inform the decision, and we knew what research to conduct to collect the data.

Therein lies the power of the decision-first approach to user research. With the decision-first approach, user research does not have to cast a wide net in the hope of getting some valuable information. Instead, the research is in the service of the data … and the data is in the service of the decision (our success). In other words, user research becomes focused on gathering data that will inform actions.

The decision-first approach ensures that user research is in the service of our success. User research becomes focused on gathering data that will inform actions.

We conducted the research and here were some of our findings:

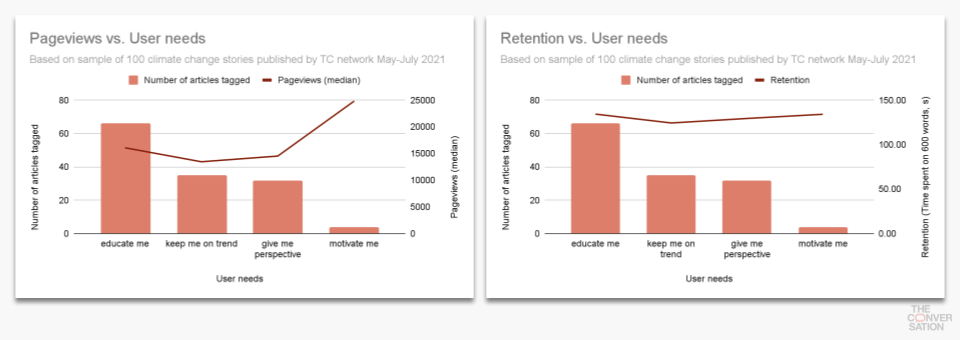

- 1-1 interviews revealed that our climate users had four key needs: educate me, give me perspective, keep me on trend and motivate me.

- The survey revealed that ‘motivate me’ was the greatest need, followed by ‘educate me’.

- Analytics revealed that what survey participants told us about their needs matched what they were reading on the site.

- Tagging of climate articles revealed a mismatch between content production and user needs. While ‘motivate me’ was the greatest need, it was also the most underserved by our coverage.

Here’s how those findings informed our decision, including two key products:

Our climate editors published more ‘motivate me’ type content such as guides and solutions journalism. Interest in those stories was, as expected, very high.

We relaunched our weekly climate action newsletter to further serve the ‘motivate me’ need. Our Imagine newsletter deep-dives in one climate issue every week, covering it with a solutions lens. Imagine is now one of The Conversation’s topic-specific newsletters with most subscribers.

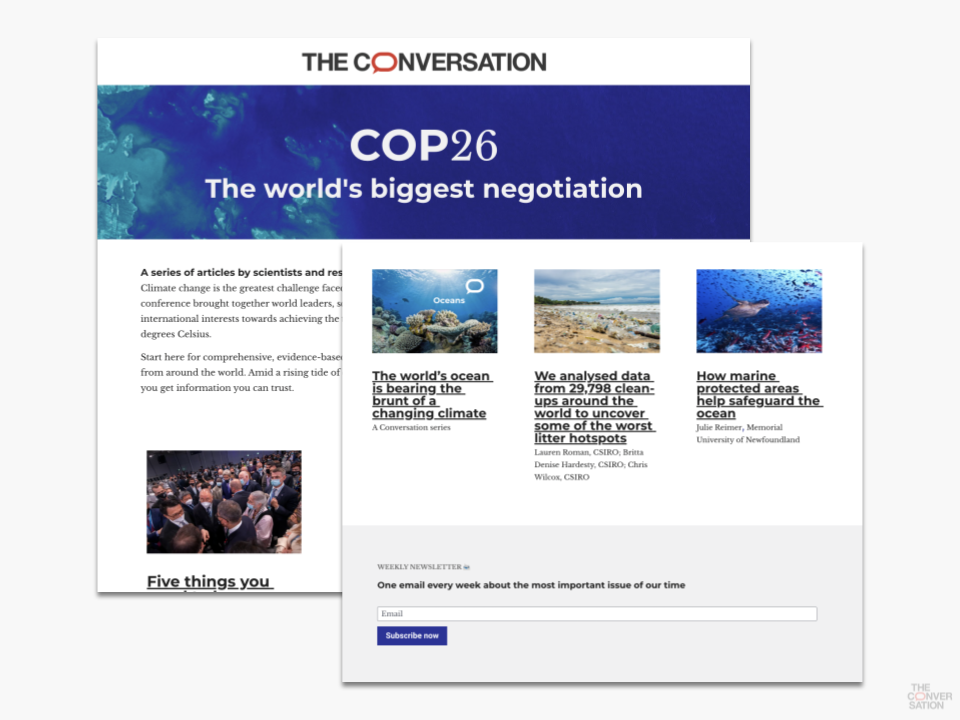

We also designed and launched an entirely new landing page to package our COP26 coverage. This product served the ‘keep me on trend’ need by making our latest COP26 coverage easily accessible in one place. The landing page also acted as a lead page for Imagine. It had a conversion rate of 10% at one point, which is the highest conversion rate ever recorded across The Conversation.

Our move from the research-first to the decision-first approach to user research has made our research process more efficient, unlocked the collection of more valuable data, and informed multiple products. All the resources and time we devote to user research now leads to collecting data that inform decisions … decisions that bring added value to our users and help us deliver on our business goals.

This article is based on a masterclass Khalil gave as part of INMA’s series on how to build customer-informed products. Find more of Khalil’s work on Linkedin.