Eric Le Braz is a journalist, previously taking editor-in-chief roles at Harvard Business Review & Prisma Media, as well as a consultant, reporter and lecturer.

We teach it to budding journalists, we recommend it as consultants and we’ve made use of it to write content for as long as we can remember. But today’s the day that we turn away from the famous inverted pyramid. Times have changed, and the arrival of paywalls means it’s time to turn to editorial narration, replacing the traditional pyramid with… an hourglass.

I’m no “locavore” (a French word referring to someone who only ‘eats locally’, consuming things from the region in which they live). For years I lived in Bordeaux without subscribing to Sud-Ouest (the main regional news media in the south-west of France). Of course, I’d buy the odd paper when a headline caught my attention. But, although subscribed to half a dozen other publications, I’d always stood my ground with Sud-Ouest and forced myself to deal with all the premium content that I couldn’t access.

I admit that, as a wanna-be Bordelais, I should really be reading Sud-Ouest in all its full glory. But I was never quite convinced.

It didn’t have that spark to make me click.

Then, one day, I cracked. I clicked-through and subscribed… and it was all thanks to a single article. A few perfectly curated lines of text persuaded me into an impulsive purchase. And it’s at this moment that I discovered the impressive force of ‘the hourglass’.

- What happened?

- What made me click?

- And what do you mean by ‘the hourglass’??

To find out more, you’ll have to subscribe to The Audiencers! ;)

…

I’m only joking. But imagine – right after my smiley, the text fades into a paywall, only available to those who fork out some cash. No subscription, no access. Just the introduction to a story that stops on a cliffhanger. It’s this that makes the hourglass effect so effective.

The fact that I subscribed to Sud-Ouest that day was down to this technique. I was caught, hook, line and sinker, to the point that I needed to pay to read on.

Let me explain.

We were mid-lockdown, vaccines were starting to be rolled out and I was desperately trying to find a slot in Bordeaux to get my jab. The only option however was to hop on the train to Arcachon (a small town an hour from Bordeaux). Otherwise no vaccine. But why Arcachon, I wondered. So, I decided to look it up, typing “Arcachon + vaccine” into Google. Which is how I came across this article:

“

“Why Arcachon has become the champion of vaccination”

It’s simple, not very glamorous, but highly efficient. Intrigued by this title that felt like it would answer my question, I continued reading – a lot of information but no direct response.

“At Tir au Vol, Arcachon, already more than 22,000 vaccinations had been completed by Wednesday, including nearly all the town’s population and every inhabitant aged 70+ or suffering from underlying health conditions. An impressive efficiency as the mayor, Yves Foulon explains.”

The lead-in isn’t bad either – eliciting just the right amount of fear – efficient, with one piece of information per (short) sentence, taking the form of a report. A sample that tempts me into the subject but still doesn’t answer what was promised (why Arcachon became a vaccination champion), ending with an offer to subscribe to Sud Ouest’s premium offer.

In paywalls as in love, you have to attract without revealing too much of yourself.

And so I subscribed to discover the rest, to find the answer to this promise. I was drawn towards the bottom of the hourglass.

If this was written like an inverted pyramid, I’d already have had my question answered (why Arcachon?).

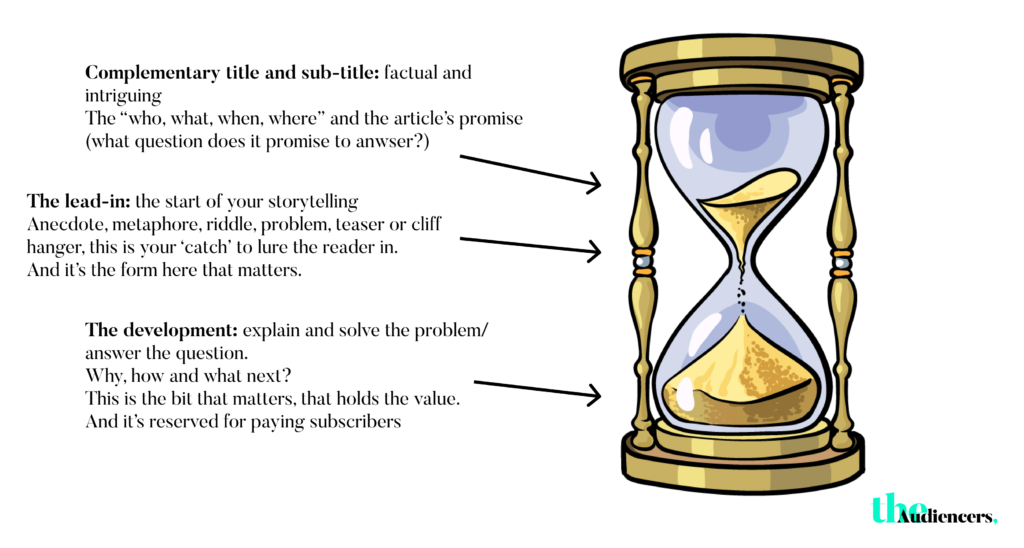

But in an hourglass, the publisher only specifies the angle from the title, often in the form of a question, but never provides readers with the answer before the paywall. They’ll outline the who, what, where and when whilst reserving the main answers to the premium part of the content – why, how, and what next?

I can already hear people in the room whispering that this hourglass is not revolutionary and that good editors know how to harmoniously distribute the three pillars that are so central to starting an article (title, subtitle, lead-in). And also that they know how to combine incentive with information to provide subscribers with additional value.

Yes. But no.

Just a quick look online and you’ll find that for an overwhelming majority of paywalled articles, the hourglass is blocked.

- Firstly because we often provide far too much information in the title and subtitle (the 5 W’s in the inverted pyramid), which ultimately reduces our desire to scroll down. We’re blocked at the top of the hourglass

- Secondly because the lead-ins are often forgotten and tend to to be a simple rephrase of the subtitle

- And finally because the paywall cut off is often badly placed. Either its too high and we barely have a chance to taste the value of the content, or it’s too low down the article and we’re already full (our questions have been answered)

There’s worse – I won’t name names but these sites are easy to spot. They’ll throw a title and a heading at you without giving a single lead-in to whet your appetite, an overall off putting strategy that only really works for the Financial Times

The hourglass is a creative constraint. I won’t deny it: an hourglass construction requires more time than an inverted pyramid. But it’s above all a new habit to form for editorial teams, which comes back to the fundamentals of journalism – journalists must make people want to read without sharing everything. It’s useless to show the whole store just in the window.

- Titles should be enticing without sinking into the “clickbait” hole (questions are still welcome as long as you don’t provide all the answers in the initial paragraphs)

- The sub-title should be informative without being a simple summary of the article. On the contrary – with an hourglass, subtitles hint at the facts, insisting on the consequences without evoking the causes. Or the inverse.

- As for the development, it should be attractive, breathtaking, funny, and create interest in the article or metaphor. The development section is definitely not an introduction. And that’s good because an article is not an essay either. To create a cliffhanger effect, it must activate the plot’s mechanisms… In short: be intriguing.

Isn’t that storytelling? Yep. And it’s not a taboo word. Albert Londres and Joseph Kessel, two famous French journalists and writers from the early 1900s, already knew all the tricks.

“In Haïfa, I received the first Israel state entry visa”

“And my plane was the first to touch down in free Palestine”

Magnificent hourglass, with no real title (the technique at the time was to deliver complementary information to the title in the subtitle), but with a breathtaking development that immediately makes you want to slam down 5 Francs to discover the rest…

“Hello, hello, Haïfa Tower? Hello, hello, Haïfa Tower?”

The 6 passengers in our little plane (named Petrel), rented in Paris to help us reach Palestine during these tough few days, listened anxiously to their pilot calling the control tower at Haïfa. On the horizon, in the haze of the heat, we could make out the coastline and the snow on Mount Hermon.

The pilot held his headphones tighter to his ears, before turning his bird-like profile towards us.

“The orders are to land at Haïfa” – he said.

I looked around at my fellow passengers and felt the worry that each of us shared. It was Tel-Aviv where we wanted to land. Tel-Aviv belonged entirely to jews. In Haïfa, the boarding place for British troops, what would be done with us? Those who had been refused a British visa.

“Insist that we land in Tel-Aviv” – I pleaded to the pilot.

He turned his head, telling me that it’s a fact: Haïfa or nowhere.

A dark-haired man, sitting behind me all nervous, almost groaned. To have waited for this for 2000 years and maybe for nothing…

I’ll stop here because there are at least the same number of sentences until we get to the scene where he receives the visa, as announced in the title… My point is that 20th century press were already using hourglass structures, plus they didn’t hold back from storytelling techniques… and didn’t produce impoverished journalism profiled by algorithms and SEO.

SEO, let’s talk about SEO. It’s not necessarily the enemy of this form of editing, because the hourglass naturally meets several SEO criteria (and it was indeed by typing “Arcachon + vaccination” that I found my article).

- If the title includes your promise, it’ll look very similar to the question being asked by a user when searching on Google. The URL, in particular, will therefore be very effective for search.

- Even better: it’s obvious that keywords have their own place in editing. The richness of vocabulary created by layers of complementary information will be a priori seen clearly by these algorithms

And what about the inverted pyramid? It won’t likely have the same fate as the one of Cheops (which remains largely intact), more likely it’s destined to be forgotten like the festoons of the copyist monks or the Nokia 3310.

It may only survive in unique situations:

- The pyramid will always be useful to write short reports, but publishers with only this kind of content won’t likely gain individual subscribers

- It can also survive in free media, but sparingly. Because the pyramid is as suitable for reading on a cell phone as a reproduction of Veronese’s “The Wedding Feast at Cana” in paperback. It just doesn’t work. The text that used to flow naturally in print quickly becomes unreadable

- New formats such as ‘listicles’ or ‘smart brevity’ (popularized by Axios) as well as their multiple variations

I digress. But new formats aren’t necessarily incompatible with the hourglass construction. But that’s another story…