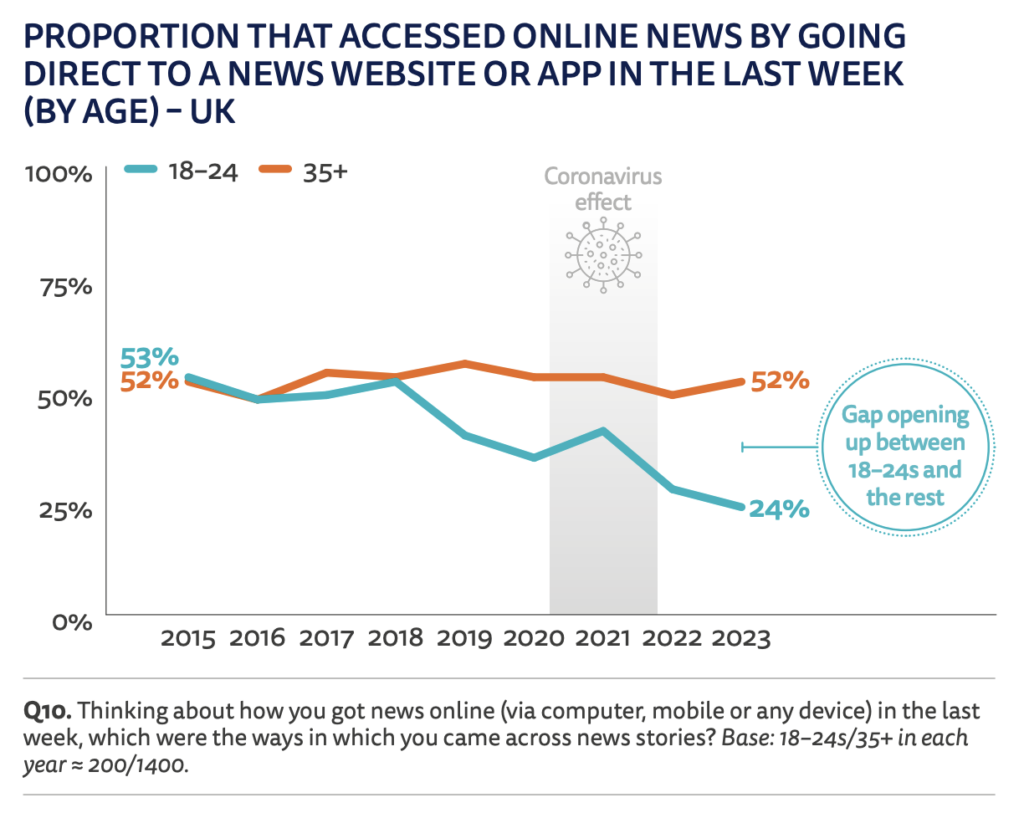

One of the greatest disconnects that we see in the news today is that we’re losing younger generations. Just look at Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023 for instance, which shows that since 2008 online news sites have lost 50% of their youngest audiences, while the older demographics have remained fairly stable.

Of course, it’s easy to conclude that this is because young demographics don’t care about the news and just want to spend their time on TikTok… but that would be wrong. Think about what has happened over the past decade. We’ve seen young demographics demand more action in terms of climate change. We’ve seen how young demographics are the strongest supporters of #metoo and are the most vocal about how it impacts them. It’s also the younger demographics who are out there protesting against the many war crimes and human rights violations we see around the world.

It’s also the youngest demographics who are the most worried about what is happening. They are the ones facing the housing crisis, and the ones worrying about jobs in a future that is becoming more and more automated, as well as bigger issues like the loss of biodiversity. It’s getting so bad that in a 2020 study, reported by The Guardian, when interviewing thousands of under 35 year olds living in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK about the idea of having children, “an overwhelming majority (60%–80%) reported that they were either postponing or entirely abandoning the idea.”

It would be a mistake to think that ‘young demographics don’t care about news, and just want to spend their time on TikTok’. It’s actually the exact opposite. Young demographics care more than any other demographics. But this also illustrates the problem we have in the newspaper industry around conversions.

Why is it that the demographic who care and are the most active are the ones moving away from newspapers, while the demographics who are the least active are the ones who stay?

The answer can partly be explained by the way we do journalism, and how we define that role in society.

There is a wonderful (adapted) quote that originates from a 1974 book by the two journalists, Sam Kinch and Stuart Long, called: “Allan Shivers: The Pied Piper of Texas Politics”. It says:

If one person says it’s raining, and another person says it’s not. Our job, as journalists, isn’t to cover what these people said, but to look out the window and see what is actually going on.”

You’ve probably heard this quote before, but what many don’t notice is that it also perfectly captures this generational divide. You see, older generations look at newspapers and journalism as being about the first part. They look at us as sources of information, and as a place where news is reported to them. In other

words, they value that we cover “that one person says it’s raining, and another person says it’s not.”

But the younger demographics live in an entirely different world. For them, information is everywhere. They are inundated by it. And so they don’t need journalists to tell them what different people are saying. Instead, younger demographics require a higher level of journalism. They require newspapers to figure out what the issues are and to put the effort and expertise into investigating this news, rather than just reporting on it. They want us “to look out the window and see what is actually going on.”

> To add to your reading list: How publishers can grow with the youth: takeaways from the Valuable Young Audiences report

And this isn’t just theoretical.

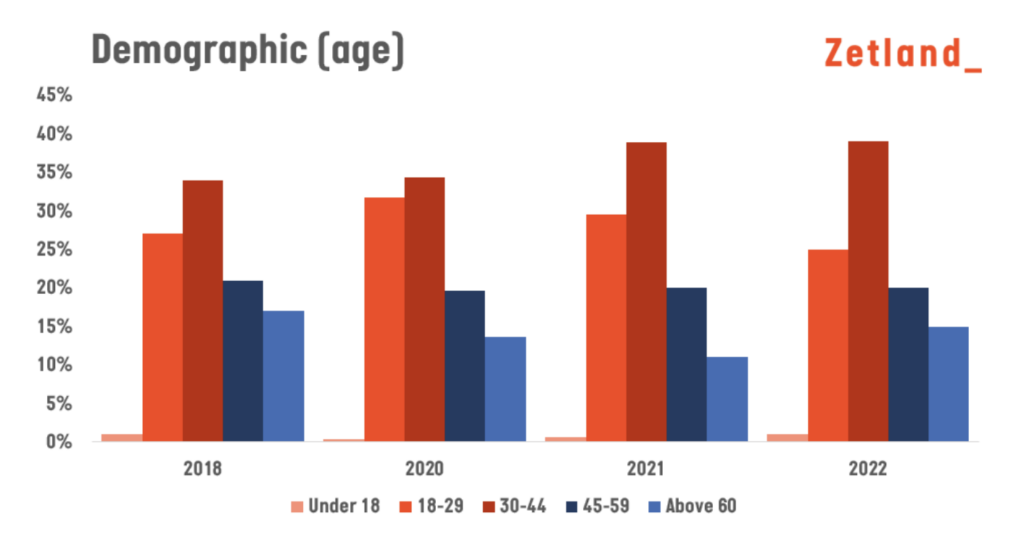

One example of a publisher already doing it is the Danish Zetland. Their journalistic focus is not to merely write 100 news articles per day, reporting on what different people say. They are doing this other form of journalism, and as a result, they have a very strong young audience – 65% of their readers are below 45.

There are of course other factors at play, but changing the journalistic focus is a really important step. The younger demographics represent our future audiences. If we can’t convert them, we don’t have a future.